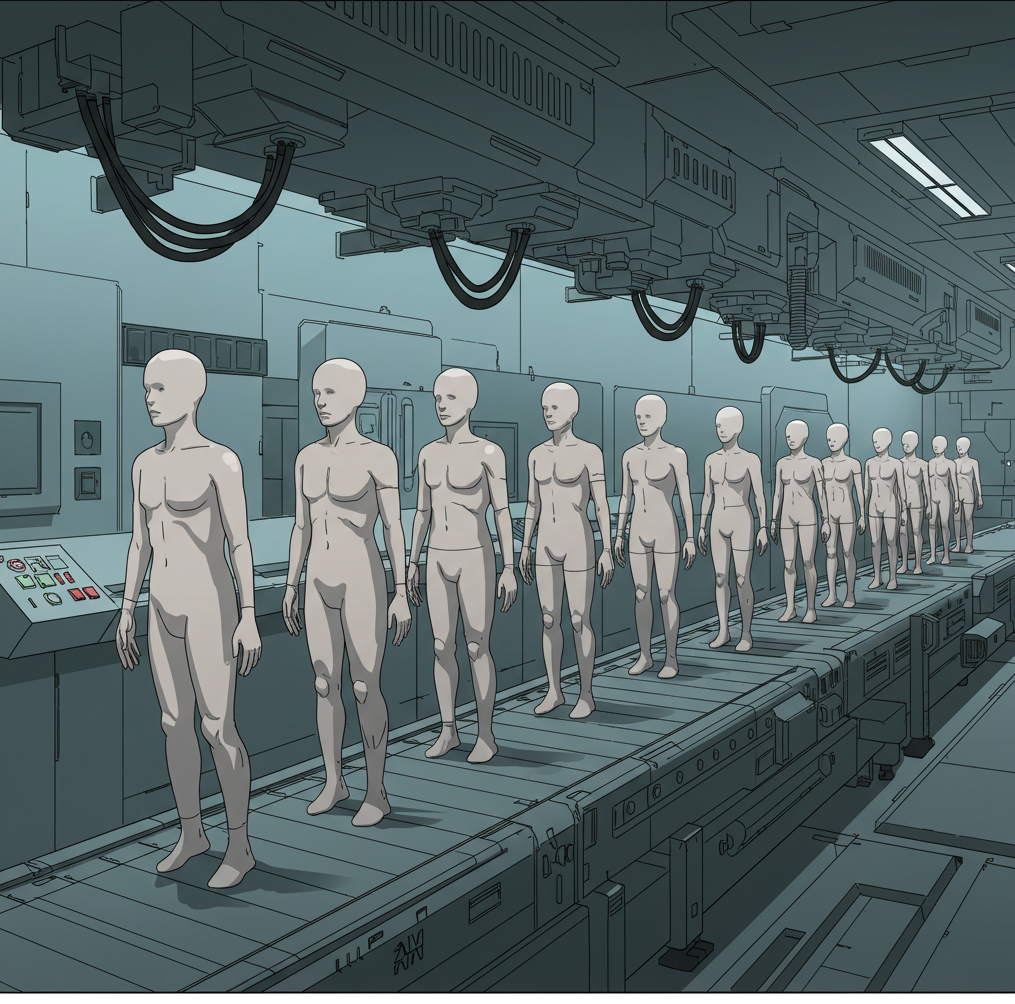

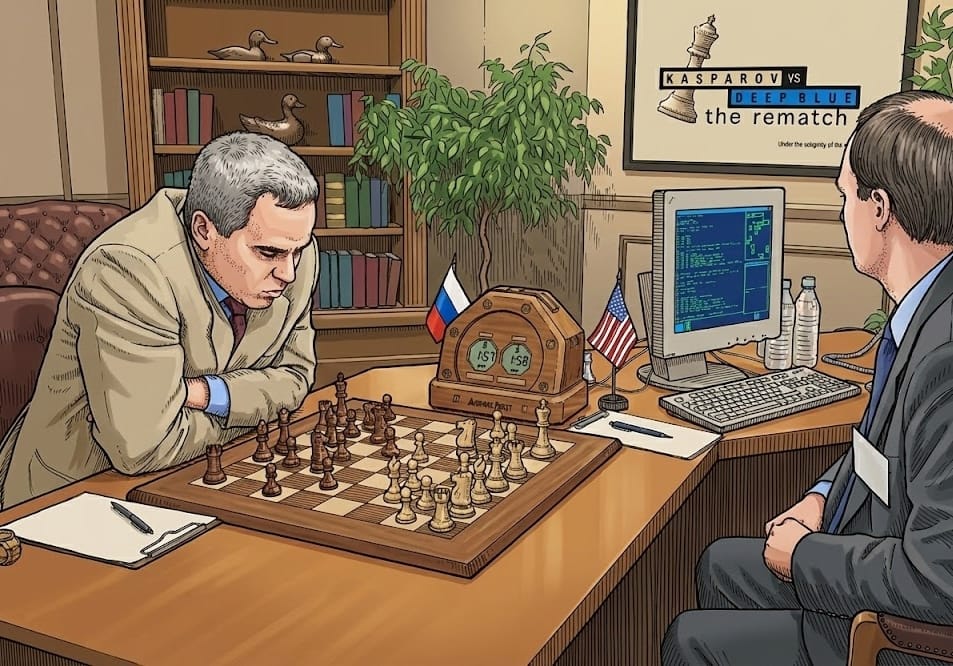

Engines of Arbitrary Power: Who Controls the Robot Army?

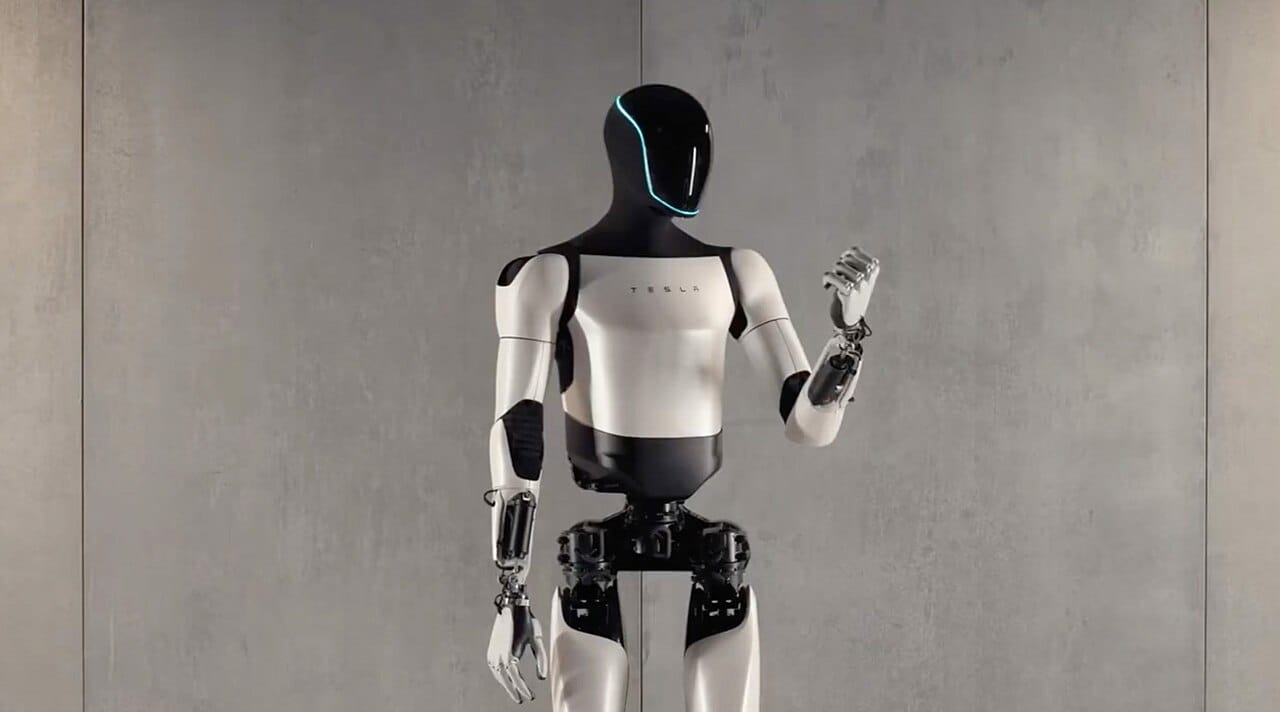

In late October 2025, during Tesla’s latest earnings call, Elon Musk told shareholders he needed a compensation package potentially worth up to $1 trillion because he didn’t feel comfortable building “a robot army” without maintaining strong influence over the company. The proposal would give him additional voting shares, ensuring he could not be sidelined by Tesla’s board or future investors as the company’s robotics ambitions expanded. The phrasing was striking, since the Optimus project has generally been described as a factory and household assistant, not a weapon or a soldier. “If we build this robot army,” he asked, “do I have at least a strong influence over that robot army?”

This sounds like something out of a comic book, but it speaks to the era we are entering. Whether or not one takes his phrasing literally, the fact that one of the most powerful industrialists on Earth is starting to worry about who controls all these robots is telling. We appear to not only be at the edge of creating human-level artificial intelligence, but also of providing it with a functional body. The near-term consequences of that shift deserve greater attention.

The conversation about humanoid robots has largely centered on economics and the transformation of labor markets. These are important questions. But we haven’t yet seriously discussed what happens when bipedal machines that can open doors, climb stairs, and manipulate objects become widely available to institutions whose core function involves the application of force.

The fear of concentrated coercive power is not new. The Founders of the United States debated intensely about whether a standing army could coexist with a free republic. They had seen what permanent militaries had done in Europe, how kings and parliaments used professional soldiers to enforce obedience and suppress dissent. They concluded that liberty could not endure if the means of coercion were separated from the people themselves. The idea of a citizen militia, however imperfect in practice, was seen as a safeguard. Defense was to remain a civic duty, not a centralized instrument. Madison warned that armies in time of peace are dangerous to liberty, and Jefferson called them the engine of arbitrary power.

President Trump’s recent use of federal forces and National Guard units in American cities, sometimes over the objections of governors and in the absence of clear emergencies, has revived old concerns about the limits of executive power and the danger of turning instruments of defense inward. His administration’s immigration raids have intensified those fears. ICE agents have appeared in masks and unmarked uniforms during arrests, leading several states to ban the practice as a step toward preventing a “secret police.” In the summer of 2025, a federal judge ruled that Trump’s deployment of active-duty troops to Los Angeles violated the Posse Comitatus Act, the nineteenth-century law designed to keep the military out of domestic policing. These episodes are reminders that the concentration of coercive power has never been merely theoretical.

The United States still relies on layers of human restraint to keep that danger in check. Civilian control of the military, the professional ethics of officers, and the loyalty of soldiers to American cultural ideals rather than to individuals have all served as quiet but essential safeguards. The system depends on the consent and conscience of those empowered to use force. Generals can refuse unlawful orders. Soldiers are trained to see themselves as protectors of the republic, not enforcers of a ruler’s will. These human-in-the-loop intermediaries, and their capacity for moral refusal, are what stand between self-government and dictatorship in large measure.

It seems inevitable that autonomous robots will be used by both the armed forces and the police eventually, though probably in different ways and on different timelines. This has more to do with incentives than ideology. Once a technology exists that can reduce risk, expand capacity, or lower costs in coercive work, institutions built around those goals will likely adopt it.

Recent developments already point in that direction. In July 2025, the U.S. Army tested an autonomous ground vehicle known as ULTRA during Exercise Agile Spirit 25 in Georgia. It navigated rough terrain and carried supplies for mortar units without a human driver. The Army has also awarded new contracts to startups building self-driving squad vehicles for infantry formations. On the domestic side, police departments have been experimenting with robotic systems of their own. In Los Angeles, the LAPD has tested a Boston Dynamics robot dog for standoffs and building entries. The New York City Police Department has redeployed its “Digidog” for patrols and surveillance, and San Francisco briefly approved armed remote-controlled robots before public backlash forced the city to reverse course. Each step has been justified as a safety measure, but together they mark a transition from theory to practice.

For the military, the logic is straightforward. Modern warfare is already partly robotic. The war in Ukraine has accelerated this trend. Drones are increasingly taking over reconnaissance, targeting, and even direct combat roles once reserved for soldiers. The move from remote control to embodied autonomy is a continuation of that shift. Humanoid or general-purpose robots that can patrol, clear buildings, handle logistics, or operate in environments unsafe for humans would be irresistible. Once one major power deploys such systems effectively, others will have little choice but to follow. The old logic of deterrence and arms races will apply: technological restraint by one side only increases vulnerability to another’s ambition. The military’s pursuit of efficiency and advantage will make the adoption of humanoid systems not just appealing but almost unavoidable.

Policing is more complicated but points in a similar direction. Departments around the world already use semi-autonomous robots for bomb disposal and surveillance. As humanoid models become cheaper and more capable, the temptation to experiment will grow. The argument will be that they reduce risk to officers, limit human error, and provide perfect records for accountability. These moves will be controversial, but public oversight is rarely vigilant for long. American police forces have already adopted military-grade weapons and vehicles, often over local objections, and surveys show that most citizens remain uneasy with that level of militarization. Yet the equipment stays, justified by safety and necessity. The same logic will smooth the path for robots.

Police robots might first appear as unarmed assistants in search and rescue, crowd management, or disaster response before mission creep leads to enforcement tasks. The transition from helper to enforcer will likely happen gradually, each step justified by safety or efficiency. Once institutions begin to rely on machines that do not tire, question orders, or unionize, their doctrines will shift around that reliability.

Decentralization has long been a bulwark against authoritarian abuse. Thousands of local agencies, each with its own leadership and accountability, make it difficult for any single regime to command them all. There is no national police force under direct executive control, and local officers answer to mayors, sheriffs, or city councils. This fragmentation limits a president’s ability to enforce ideology uniformly. It is why calls to “send in the feds” immediately raise questions about legality and consent: law enforcement in America is deliberately balkanized. If control systems link thousands of units through centralized software, the same decentralization that makes policing hard to coordinate today could vanish, enabling nationwide control.

History offers many cautionary tales of what can happen when coercive power becomes too centralized. The most chilling example remains Nazi Germany. The regime built its authority on an internal police empire made up of the Gestapo, SS, and Ordnungspolizei, which reached into every neighborhood. The Wehrmacht fought wars abroad, but inside Germany it was the police who enforced ideology, eliminated dissent, and administered terror. By combining the army’s organization with the police’s intimacy, the Nazis achieved total control: the army conquered territory, and the police occupied society itself. Power became local and familiar, no longer distant or abstract, something felt in every home and visible on every street.

Recalling this history clarifies the mechanics of domination. Totalitarian power thrives when coercive tools are centralized. The means need not be as brutal to achieve the same structural effect, obedience enforced by systems rather than people. As we stand on the threshold of deploying humanoid robots in both military and policing roles, the risk is not that we will become Nazis, but that we will recreate their architecture of control through code and convenience.