On Randomness

In the autumn of 1927, physicists gathered in Brussels for the fifth Solvay Conference. The photograph from that meeting has become iconic: three rows of the greatest scientific minds of the century. Marie Curie, Max Planck, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Paul Dirac. And seated in the front row, center, Albert Einstein.

The occasion was quantum mechanics, the strange new theory that had overtaken physics. Experiments had revealed something troubling. Physicists could fire electrons through an apparatus, one at a time, prepared identically each time. And yet each electron landed at a different spot on the detector.

In classical physics, this would mean something differed between trials that the experimenters had failed to measure. But if you fire thousands of electrons and record where each one lands, a pattern emerges, and newly developed mathematics could predict that pattern with stunning precision. If the variation were mere experimental noise, some uncontrolled difference between trials, why would the distribution be so perfectly predictable? Bohr and Heisenberg concluded that there was no hidden difference between one electron and the next; the theory was complete, and probability was fundamental. For many, that settled the question.

This was the Copenhagen interpretation. Reality, at its most fundamental level, is irreducibly random.

Einstein could not accept this. His objection was not to the strangeness of quantum mechanics; he had made peace with plenty of strangeness in his own work on relativity. What troubled him was deeper. A world with uncaused events, he felt, was not a world that made sense. It was not clear to him that such a world was even possible. "God does not play dice," he famously remarked. The line is often quoted as a kind of stubbornness, an old man's refusal to accept new ideas.

The debates between Einstein and Bohr stretched over years, through letters, conferences, and thought experiments. Einstein would propose scenarios designed to show that quantum mechanics was incomplete, that there must be hidden variables beneath the probabilistic surface. Bohr would find the flaw in each proposal, defending the completeness of the quantum description. By the time Einstein died in 1955, the consensus was that Bohr had won. Quantum mechanics needed no deeper layer. The randomness was real.

Then, in 1964, the physicist John Bell proved a theorem that seemed to settle the matter. He showed that quantum mechanics forced a choice: either you give up hidden variables, or you give up locality. You cannot have both and still match the predictions. Over the following decades, experiments confirmed that quantum mechanics was right. Most physicists chose to give up hidden variables.

Ever since, the popular conclusion has been that Einstein was wrong. Not just wrong about the details, but wrong about the nature of reality. The universe was not a clockwork. At its foundation lay irreducible chance, events without causes, outcomes that nothing determined. Ontological randomness had been rigorously confirmed.

Yet several fully developed interpretations—Everett's many-worlds, Bohm's pilot-wave theory—reproduce quantum predictions without invoking a single causeless event. These are not fringe proposals; they are serious frameworks pursued by serious physicists. The Copenhagen interpretation is not a finding forced on us by the evidence. It is one choice among several.

The popular conclusion, I want to argue, is mistaken. Not because the experiments were flawed, and not because quantum mechanics fails as a predictive theory—it remains one of the most successful theories in the history of science. The conclusion is mistaken because it does not follow from the evidence. The leap from "our best theory is probabilistic" to "reality is ontologically random" is not a scientific finding. It is an interpretation, and an incoherent one at that.

This is not a retreat to classical physics, nor a denial of what quantum mechanics has taught us. It is a commitment to the principle that has underwritten the entire scientific enterprise: that reality is an interlocking structure of causes, that it is intelligible, and that cause and effect continue even where we cannot yet see them. Einstein's intuition was not a relic of nineteenth-century thinking. It was a clear-eyed recognition of what science requires to be possible in the first place.

To see why ontological randomness cannot be established, consider what evidence for it would look like. If an event has a cause we cannot access—because it operates at a scale beyond our instruments, or through mechanisms we have not yet discovered—the event will look exactly like a causeless event. There is no observation that distinguishes "random because uncaused" from "unpredictable because the cause is hidden." Unpredictability is evidence of the limits of prediction. It is not evidence that prediction is impossible in principle.

To claim that an event is truly causeless, we would need to verify the nonexistence of all possible causes. But causes could be hidden in indefinitely many ways: in variables we haven't conceived of, at scales we cannot probe, in dimensions we cannot access. The claim of ontological randomness requires not just that we have found no cause, but that we have established none exists. This is not a claim evidence can support. You cannot confirm an absence that extends beyond your ability to search.

I suspect this concept is empty. Human language permits us to construct sentences that parse correctly but designate nothing. "What is north of north?" follows the rules of English syntax. It has the grammatical form of a question. Yet it does not describe a possible state of affairs; there is nowhere for the mind to go in attempting to answer it. The sentence is not false. It is empty. I suspect "the event had no cause" belongs to this category. We understand each word individually. We understand the grammatical structure. And so we assume we understand the proposition. But the concept of a causeless event is defined precisely by the absence of anything to grasp. It is a hole in the shape of an explanation.

The structured view—the view that reality is thoroughly governed by causes—is not merely defensible. It is strongly favored by the total weight of evidence. Science does not proceed by single observations or isolated experiments. It proceeds by approaching the same underlying reality from multiple angles, using independent methods, and checking whether the results converge. When they do—when different instruments, different theoretical frameworks, different researchers all point to the same conclusion—we gain confidence that we are tracking something real. This is triangulation: the reinforcement of belief through convergent evidence.

The entire history of science is, in this sense, a massive triangulation in favor of the structured view. Every successful explanation, every confirmed prediction, every technology that works, is a data point in favor of the structured view. The polio vaccine works because viruses follow biological rules. The bridge holds because steel obeys physical laws. Semiconductors switch because electrons behave predictably at the quantum scale—the very scale where we are told causation gives out. Nowhere in the history of science has the bet on structure failed to pay. This is not a mere methodological assumption we adopt for convenience. It is an empirical finding, one of the most robust we have.

Now consider what the Copenhagen interpretation asks us to believe. It asks us to accept that at one particular scale—the quantum scale—the otherwise universal finding that things have causes suddenly fails to apply. The structure that held everywhere else, that has been confirmed by centuries of convergent investigation, gives out precisely at the point where our instruments blur.

This should strike us as suspicious. When a pattern holds everywhere we can see clearly and fails only where we cannot see well, the parsimonious hypothesis is that our vision is the problem, not that reality has changed its character. Science is a bet on structure. That bet has the same success rate as quantum mechanical predictions: perfect, within the domains we can test. To abandon the bet at the quantum scale is not to follow the evidence. It is to abandon the principle that generated the evidence in the first place.

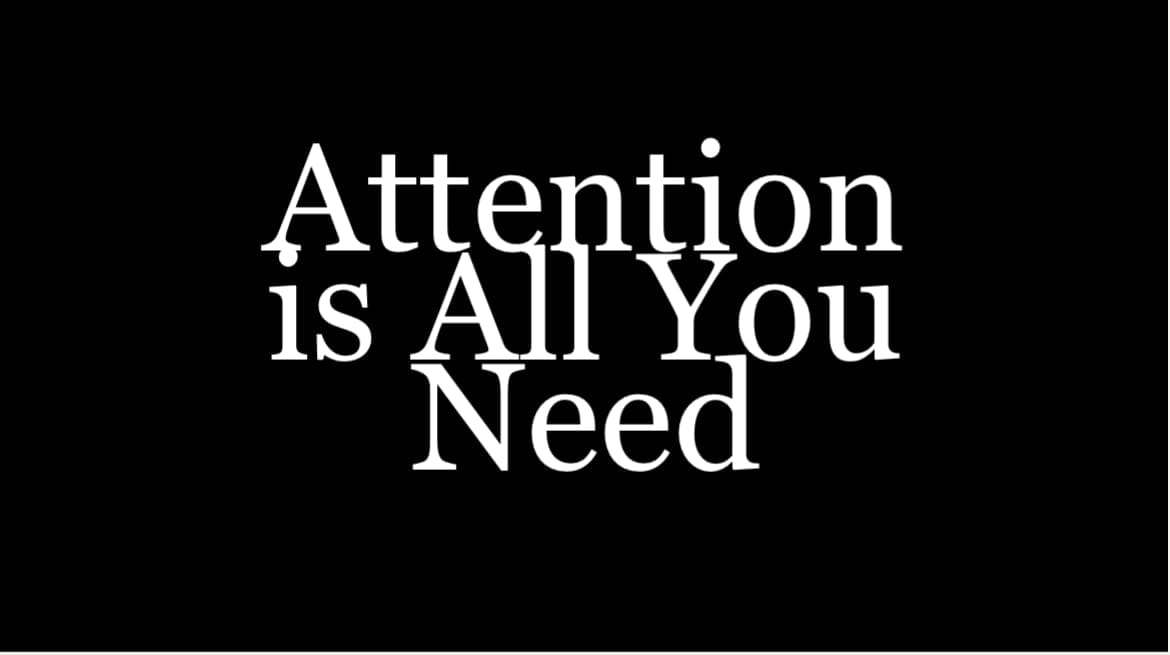

There is another way to see this. What is it to understand something? At the most fundamental level, it is to recognize pattern: to detect regularity, to model structure, to compress experience into representations that capture what persists across instances. Intelligence, in this sense, is structure-detection. The mind reaches into the world and finds purchase wherever there is rule-governed regularity to grip.

But a pattern is not merely a sequence that happens to repeat. A pattern is a regularity with a source, a recurrence generated by underlying structure. When we recognize a pattern, we are implicitly modeling whatever produces it. A truly causeless event, by definition, would exhibit no pattern—not because the pattern is hidden, but because there is nothing generating one. Such an event would be unintelligible in principle, not merely in practice. It would lie outside the space of what minds can engage with, because minds engage with structure, and causelessness is the absence of structure.

This suggests a deep coherence between the nature of intelligence and the nature of reality. Intelligence can only exist and operate in a world with structure. A world containing genuine ontological randomness would be, to that extent, a world with regions that cannot be understood—not because we lack information, but because there is nothing there to understand. The existence of minds, the success of science, the very possibility of knowledge: these all point toward a reality that is thoroughly structured, with no voids where the rules give out.

The word random does have legitimate uses, and I do not wish to deny them. When we say a process is random, we typically mean one of several things: that we lack the information to predict it, that it is best modeled statistically, that it is highly sensitive to initial conditions, or that it is chaotic in the technical sense. These are useful concepts. They describe real features of our epistemic situation and real structural properties of certain systems. A coin flip is random in the sense that we cannot practically predict it, but it is not causeless; it is determined by the mechanics of the flip, the air resistance, the surface it lands on. We call it random because we lack access to the determining conditions, not because those conditions do not exist.

The error is to slide from this ordinary, epistemological sense of randomness to the extraordinary, ontological sense—to move from "we cannot identify the cause" to "there is no cause." This slide is not justified by any evidence, because no evidence could justify it. It is a confusion born of taking our limitations for features of reality.

What follows if ontological randomness is indeed incoherent? Not that the universe is predictable. The causal structure can be vastly beyond our ability to model, calculate, or foresee. Determinism does not entail predictability. A system fully governed by rules can still be chaotic, sensitive to conditions we cannot measure, complex beyond our computational reach. The claim is not that we can know everything. The claim is that there is something to know—that the question "why?" always has an answer, even when we cannot find it.

This is what Einstein saw, and what I believe he was right about. Not the specific form of hidden variables he hoped for—Bell's theorem rules out the local version—but the deeper principle: that reality is structure, that the phenomena we observe are entailed by underlying rules, that there are no voids where things simply happen for no reason. The Copenhagen interpretation looked at the limits of its instruments and declared it had found the limits of causation. But every previous boundary turned out to be ours, not the world's. There is no reason to think this one is different.