AI Risk and the Banality of Evil

In 1961, Hannah Arendt sat in a Jerusalem courtroom watching Adolf Eichmann testify from behind bulletproof glass. The German-Jewish philosopher had fled Nazi Germany decades earlier, leaving behind her homeland and her doctoral studies. Now, reporting for The New Yorker, she found herself face-to-face with one of the Holocaust's chief architects. What unsettled her was not a figure of demonic intent, but a former railroad clerk whose administrative skill had enabled the machinery of genocide.

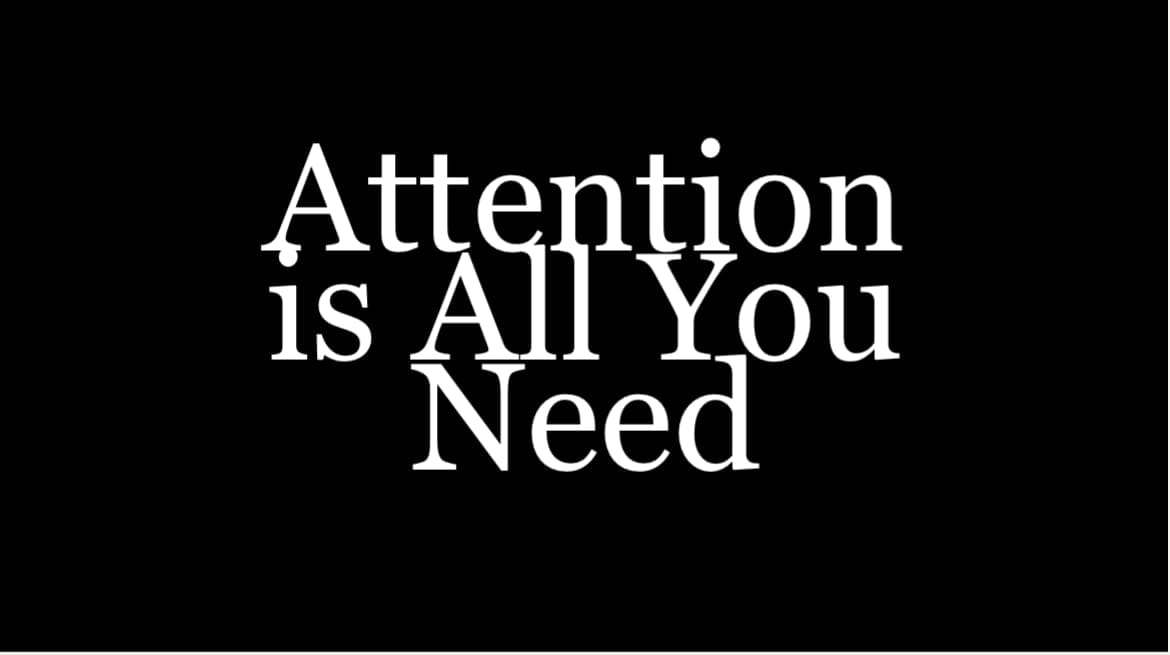

Competence is always dual use, and artificial intelligence is dangerous for precisely this reason. Some readers may expect a lengthy discussion of machines themselves pursuing goals. That is a real debate, but I believe it is not today's danger. The architectures of today are powerful but inert; they are not able to continually learn on the job. Misuse is the risk at hand, which is the topic of this essay.

The AI safety community largely splits into three overlapping camps. So-called "accelerationists" cheer rapid deployment, convinced the dangers are overstated and the gains of progress outweigh what risk there is. Conservatives call for delay: time to test, regulate, and understand sudden jumps in capability. And advocates of open source and "open weights" urge transparency, warning that closed systems concentrate power and stifle scrutiny. Their opponents counter that releasing powerful models is less like publishing research and more like leaving plutonium in a public square.

But beneath these arguments lies an old philosophical debate: the question of what humans do with power. Rousseau believed that, freed from distortion, people incline toward cooperation. Hobbes believed the opposite: that humans pursue dominance and self-interest, and peace comes only from a counterforce. Your inclination here shapes how much faith you have in giving powerful tools to the public. But science has largely settled this debate. We evolved in competitive bands where resources were scarce. Natural selection rewarded those who schemed for advantage, formed coalitions, and exploited opportunities. Those drives remain: the hunger for wealth and power, the instinct to rationalize harm, the impulse to dominate when we think we can get away with it. Most people restrain themselves through conscience and consequence. Some do not.

And competence magnifies the danger of those few. Hitler would have been nothing without the Luftwaffe's aircraft engineers, the railroad managers who scheduled deportation trains, the chemists who developed Zyklon B, and the bureaucrats who organized genocide with industrial efficiency. A tyrant can wage a war of conquest only if he has a competent army. A terrorist can spread fear only if he can competently organize violence. A hacker who delights in destruction needs skill to build a virus. The question isn't whether such people exist, they do, but whether we will hand them the most powerful competence engine ever built.

Modern AI systems make that prospect more likely because their safety is fragile. Guardrails are layered on top of the model's core capabilities. That makes them shallow compared to the intelligence underneath. Stripping them away is easier than building them in. When Meta's research-only LLaMA model leaked online in March 2023, it spread within hours across forums. By morning, hobbyists were running it on consumer GPUs. Researchers showed how quickly its safety limits could be removed: a modest dataset of dangerous prompts, a single high-end graphics card, and the model would produce what it was trained to refuse. Each leak becomes a permanent vulnerability, and safety cannot be retroactively patched into weights already in the wild.

Biological brains suggest a possible solution. Our moral intuitions are spread across billions of neurons behind a calcium-reinforced skull. You can't rewire them with a scalpel without destroying the patient. We might develop digital equivalents, architectures and environments that make tampering destructive or prohibitively costly. Hardware developments suggest this direction is feasible. New graphics processors can boot into secure modes, anchored in the chip itself, that verify the model being loaded and refuse unauthorized versions. This doesn't prevent leaks, but it could make running rogue models in commercial data centers far harder. The goal wouldn't be to build an impenetrable wall, but to raise barriers so misuse requires more than simply dragging files into place.

Institutions can extend that friction. Nuclear material is not mysterious, but it is tracked and monitored through strict custody. AI likely needs something similar: tracked model versions, verified software stacks, audited data centers, export controls on the most advanced processors. Already, regulators are beginning to tie market access to provenance, forcing models to carry documentation the way travelers carry passports. Critics worry oversight will choke innovation. But history shows that oversight and science can coexist. In 1957, during the International Geophysical Year, nations agreed that any Antarctic research station could be inspected by others. This did not halt discovery; it built trust and prevented military abuse. Science continued, but within structures that preserved accountability.

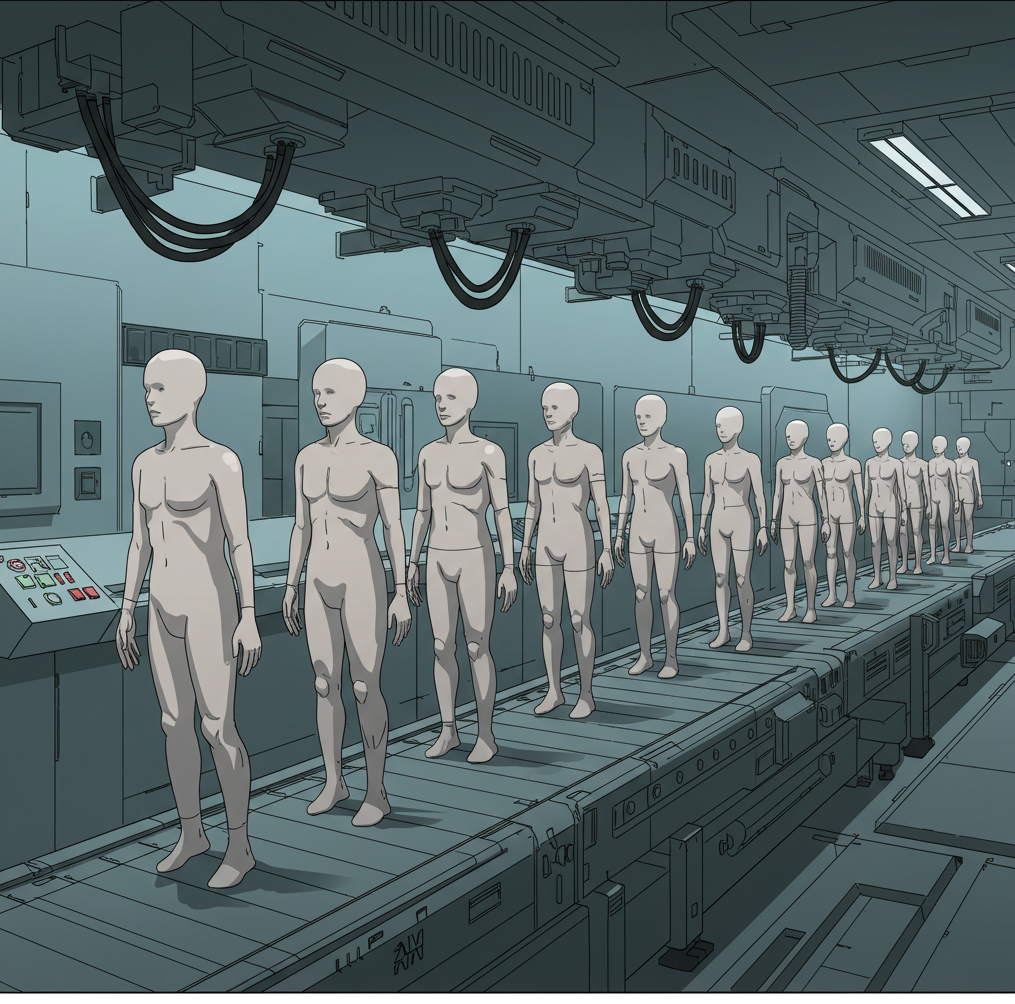

Skeptics may still say this is overreaction. The internet was an open system, after all, and civilization survived. But two differences matter. First, compression. Knowledge that once required vast libraries and lifetimes of training is now distilled into gigabytes, easy to copy and share overnight. Imagine the Library of Congress on a thumb drive, except this library doesn't just hold knowledge, it applies it. Second, automation. The internet spreads harmful ideas, but humans must act them out. AI can carry out harmful tasks directly, step by step, on command. It is the difference between finding a recipe and hiring a robot chef who cooks it instantly. Compression makes knowledge universally portable. Automation makes it instantly actionable. Together, they make competence, the master variable, more dangerous than ever before.

It is worth pausing again on autonomy. Some imagine the primary danger in AI systems is them pursuing goals of their own, slipping out of human control. That possibility cannot be dismissed, but today's architectures are poorly suited for it. Transformers trained through global backpropagation are largely static once trained. Workarounds like retrieval-augmented generation and in-context learning can patch in new information, but they do not weave it into the model's core structure. Outputs remain anchored by the frozen pretrained model.

Backprop-based systems require sweeping weight updates to learn at all. They are brittle and sample inefficient, requiring large numbers of examples. Autonomy risk is likely tied fundamentally to this state of online, continuous learning. And no one yet knows how to build this. Today's models remain inert. They can be misused in catastrophic ways, but they are not plotting ends of their own. Misuse is the clear and present danger. Autonomy remains speculative, rising only if architectures shift towards online systems.

None of these steps, hardware protections, provenance chains, oversight, guarantee safety. They only tilt the odds. They make it less likely that a disgruntled individual downloads model weights on Friday and, by Monday, has a dangerous unmonitored adviser. But tilting the odds matters.

Hannah Arendt ended her Eichmann report by reflecting on thoughtlessness: not stupidity, but the failure to imagine consequences. That is the danger artificial intelligence presents, not that it decides what to do, but that we fail to think ahead. Our history shows foresight is possible once we understand what is at stake. Competence is dual-use, and AI has given us the purest, most scalable form of competence yet. It does not care what ends it serves. That choice is ours. The clock started when the first model weights leaked online. We need urgency, and that urgency must become hardware, protocols, and law. Not just to protect this generation, but all who follow.