Schleppy AGI

Dwarkesh Patel recently published a compelling essay arguing that today's AI systems are still many years away from AGI. His core view is that they are missing key components of cognition, most importantly true continual learning. Despite impressive benchmark performance, current models aren't yet economically transformative because they can't learn on the job the way humans do. Instead, labs are "pre-baking" skills into models using Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR), constructing bespoke training environments for coding, Excel, browser navigation, and countless other narrow tasks. To Dwarkesh, this reveals a fundamental limitation. As he puts it, "Human workers are valuable precisely because we don't need to build schleppy training loops for every small part of their job."

It's a persuasive argument. But the question I keep coming back to is: is the elegant solution a hard requirement or can we sort of duct tape our way to AGI?

Consider Deep Blue. In 1997, IBM's Deep Blue defeated Garry Kasparov in a six-game chess match that captivated the world. Deep Blue did not understand chess in any human sense. It had no intuition, no internalized strategy, no aesthetic judgment. It simply evaluated millions of positions per second and searched deeper than any human could. One move in Game 2 unsettled Kasparov so badly that he accused IBM of cheating; it felt too creative, too human. But it was nothing of the sort. It was brute force, systematically exploring the possibility space. Twenty years later, AlphaZero learned through self-play, developing a fluid, intuitive style that grandmasters described as alien yet beautiful. AlphaZero played chess the "right" way. Both systems accomplished the goal of playing chess better than humans, but Deep Blue got there first. The ugly solution won.

Are we in a similar situation today?

Dwarkesh looks at the current AI landscape and sees missing categories of cognition. Labs are painstakingly constructing verification environments for individual skills, and to him this is evidence that models lack genuine generalization. Real jobs, he argues, consist of hundreds of small, shifting tasks that vary from day to day, even for the same person. You can't automate them with predefined skill sets. In a way he's recapitulating the old expert systems vs learning systems debate. Manually coding how to behave was too brittle, so it never worked.

Interestingly, his view does stand in contrast to many lab leaders. A skeptical reader will surely argue that's because they have a strong incentive to exaggerate the pace of progress, but for the purposes of this discussion, let's take their statements at face value. Dario Amodei believes the current paradigm will get us there, predicting powerful AI as early as 2026. Sam Altman and Jakub Pachocki have offered concrete timelines, an intern-level AI researcher by late 2026 and a fully automated one by 2028, backed by over a trillion dollars in infrastructure commitments. Mark Chen, OpenAI's Chief Research Officer, has pushed back on the idea that scaling is exhausted, hinting that they have made some important breakthroughs in pretraining specifically.

This perspective is not unanimous. Demis Hassabis believes additional breakthroughs are needed on the level of the transformer, and Andrej Karpathy estimates something like a decade. This camp tends to be more neuroscience-inspired, believing the current architectures are missing something fundamental.

So what's the actual bottleneck?

Dwarkesh's argument largely boils down to three problems all related to memory. First, current models are sample inefficient—they need far more examples to learn something than a human would. Second, what they learn isn't general enough to transfer across contexts. Third, they can't continue to learn on the job the way humans do.

This last problem is intrinsic to how gradient descent works. When a model learns, it adjusts billions of parameters at once, a global update that touches the entire network. This makes the system brittle; new information can overwrite old information, a problem called catastrophic forgetting. So today’s models come with a frozen pretrained brain and rely on stuffing relevant information into each prompt, called a context window. These are crude substitutes. Everything must be reprocessed with every response. There's no dynamic working memory, no graceful fading of irrelevant information, no seamless integration with long-term storage.

This matters for a number of reasons. Without the ability to integrate new information into its world model, it can only grasp new tasks superficially. It can't build on what it learned yesterday. Models struggle to navigate complex software because they can't track things the way you do. Photoshop is intuitive to an experienced user, but to a model with fragmented memory, every menu is half-familiar, every action a guess. These aren't signs of low intelligence. They're signs of a specific limitation, not dissimilar to a human disability. Blindness or deafness will make some tasks virtually impossible, but this says nothing about their underlying intelligence. Similarly, a model can be extraordinarily capable and still fail at tasks that require persistent memory.

All of this is accurate. The open question is whether it represents a hard scientific boundary or is just a matter of iterative engineering.

Human memory itself is not a single, elegant system. It's a collection of specialized mechanisms layered together by evolution. Most day-to-day learning does not instantly integrate deeply into the brain. It involves holding information in working memory, encoding episodes, retrieving associations, and slowly consolidating over time.

Seen this way, perhaps the models aren't so far from functional equivalence after all. Retrieval over long interaction histories so a system remembers what you discussed weeks ago. Persistent preference and project files injected into context. Lightweight fine-tuning methods like LoRA applied periodically rather than continuously. External memory via tool use, where models write notes to themselves and read them back. Better working-memory mechanisms layered on top of existing architectures. None of this requires brand-new science, and much of it already exists in partial form.

These solutions are undeniably schleppy. They are brittle and can fail in surprising ways. Skeptics rightly point out that unlike chess, which is a closed system with perfect information, the real world is an open environment where errors can compound. That's all true, but we are no longer discussing hypotheticals. People are already using these systems for real work. Coding agents are writing and debugging software semi-autonomously. Customer service systems are starting to handle basic help desk queries. Legal research can often be handled end to end by an extended thinking model. There's still a capability gap, but it is shrinking.

It's important to recognize that 2025 was less a year of huge new models than one of bringing the frontier to everyone at a reasonable cost. That infrastructure buildout absorbed resources that might otherwise have gone toward pushing capabilities. If progress has felt slower than expected, this is part of the reason. It's easy to anchor on the current pace and assume it's the new normal. That would be a mistake.

The hardware trajectory is significant. Nvidia’s GB300 NVL72 racks use 72 Blackwell Ultra GPUs acting as a single massive unit. Microsoft has announced the first large-scale production cluster with over 4,600 of these racks, claiming it will enable training models with hundreds of trillions of parameters and reduce training times from months to weeks. Depending on workload, this represents anywhere from a 4x improvement in training speed to a 10x reduction in inference costs compared to the previous generation. When you can throw an order of magnitude more compute at context management, retrieval, and verification, many of today's clumsy workarounds start to look far more viable.

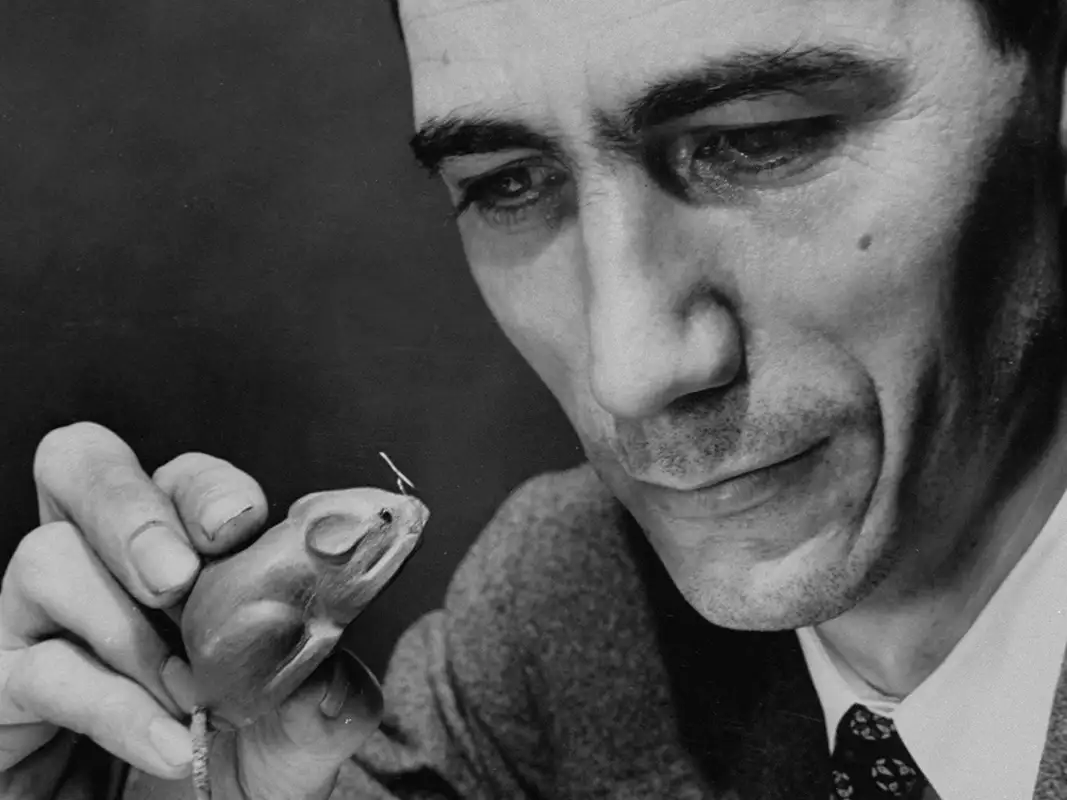

We do need solutions to memory and some degree of continual learning, but Dwarkesh may also be understating how much current models already generalize. No one built a special training pipeline for GeoGuessr, yet general models can perform at a borderline superhuman level. This requires inferring the geographic location of pictures from subtle cues like vegetation, signage, architecture, and sun angle. And long before job-specific reinforcement learning was used, models already showed remarkable capability across many professions, just from compressing the internet.

The labs' heavy investment in RLVR could be viewed less like a confession of architectural inadequacy and more like a pragmatic choice. RLVR improves effectiveness on tasks that matter commercially. It simply juices the value of current models.

The benchmark, OSWorld, provides a useful case in point of my argument. This benchmark tests models on everyday computer tasks in a virtual machine: adding page numbers to a document, exporting a CSV from a spreadsheet, configuring browser settings. Over the past year, success rates have climbed from under 10% to over 60%, approaching the human baseline of 72%. But a closer look reveals something interesting: much of this progress comes from models finding workarounds. About 15% of tasks can be completed using only terminal commands, no GUI required. Another 30% can be largely solved with Python scripts instead of clicking through menus. The benchmark was designed to measure GUI manipulation, something models are known to struggle with, but instead of failing, they just found a workaround.

This discussion largely hinges on how far these workarounds can ultimately go. The debate isn't about whether human-like continual learning would be powerful. It would be. It's about what exactly is required to cross the human threshold of reliable knowledge work. History suggests that inelegant, resource-intensive solutions arrive first, especially when the incentives are overwhelming.

Ray Kurzweil's long-running prediction of human-level AI by 2029 is relevant here. Kurzweil's track record on specific technologies is mixed, but he has been remarkably prescient about the pace and magnitude of technological progress. His law of accelerating returns is all about markets. Computing power compounds due to incentives and what’s allowed by physics. Capital, talent, and institutional effort then develop new technologies enabled by that compute.

Humans are best understood as what E.O. Wilson called a “superorganism,” similar to ants or termites. We cooperate at an unprecedented scale. And this global superorganism has slowly been turning itself toward the production of machine intelligence ever since ChatGPT arrived in late 2022. Nation-states, corporations, supply chains, research communities, and capital markets are all aligning around the same attractor. This applies immense pressure to each barrier to progress.

If the current paradigm fails to reach AGI, it will be because continual learning turns out to be a hard scientific barrier rather than an engineering challenge. But given the scale of investment, the pace of hardware progress, and the growing stack of workable approximations, I'd bet on the engineers.

It's unclear when we will get the elegant, human-like mind we are waiting for. But if history is any guide, that distinction may not matter much. When Deep Blue won, Kasparov felt it was a trick. He sensed a human creativity that simply wasn't there and accused IBM of cheating. We are likely walking into the same psychological trap. We will look at these schleppy, duct-taped systems and insist they are just parroting data or faking reasoning. We will call it a parlor trick right up until the moment it outperforms us. At that point, like Kasparov, we will have to accept that the mechanism matters less than the move.